Running my Plant Business, Sustainably

- Green Embassy

- Feb 6

- 36 min read

Updated: Feb 10

One story. 9 minutes read. We are told that plants are always good, and that is the case when done properly. We are told that more greenery automatically means a healthier planet. But behind every indoor plant is a supply chain few people ever see, and an industry built on consumption rather than care - I wrote a blog about "The Hidden Cost of Plants: Plastic Pollution from the Plant Industry", which you can add to your reading list (link).

This article is not about selling plants. I am not being paid for any product endorsement. This is unbiased. It is about questioning the systems behind them, unlearning comfortable myths, and discovering what it truly means to choose alternative products for home and for the office that fit the mission towards a better future - without greenwashing, shortcuts, or illusions.

Chapter One: It Was Fun Until It Wasn't

When I started my plant business in Lisbon, I had little understanding of the hidden realities behind indoor plant production and the consumables that support it. I began with a genuine passion for Nature and a desire to build something that gave back. Profit mattered; however, I refused to build a business where profit came first, and consequences were ignored.

I made a clear promise to work with Nature, not against it.

At the time, I believed I was doing well. I was bringing plants into Lisbon, helping businesses flourish, and designing spaces where Nature was integral rather than decorative. My service reflected what I always stood for: quality, professionalism, and no shortcuts. I made a clear promise to work with Nature, not against it.

Curiosity led me to knowledge - and knowledge is unsettling. It dismantles comfort and replaces it with responsibility. Slowly, I realised something did not add up. Something smelled rotten.

Chapter Two: Too Good To Be True

The industry narrative I was fed was relentlessly “positive”: buy more plants, consume more greenery, feel better. Influencers preached growth while saying almost nothing about how plants are produced or what that system entails in terms of waste. I see dead plants dumped in the streets every week; it's clear that something is wrong. Many of these voices were shaped by sponsorships from large growers, retailers, fertiliser brands, and pot manufacturers. They weren’t just selling plants; they were selling their credibility. And the system they upheld cared far more about selling units than about plant health or ecological balance.

Without noticing, I had been greenwashed into believing that constant purchasing was inherently good. Once I looked closer, the illusion collapsed.

Behind every plant are months - or years - of industrial cultivation: artificial lighting, synthetic fertilisers and growth regulators, plastic, resource extraction, habitat loss, cross-border transport, and intensive insect control systems. We label the consequences of this disruption as “pests", conveniently ignoring that humans are the most invasive species of all. Nature is self-regulating - until we interfere. But that is a discussion for another time.

Chapter Three: Numbers Don't Lie

Like every human-made industry, this entire plant system exists so a consumer can buy, watch a plant decline, and replace it - disposable. The numbers are stark. Roughly half of all 5.5 billion plants produced globally die within their first year after purchase. That translates to an estimated 2.75 billion plants discarded every year. Organic matter will eventually decompose; plastic will not. Nor do the emissions, resource extraction, and ecological damage quietly disappear. This is the part of the story no one sells.

The global potted plants market is valued at 32 billion euros annually. An estimated 5.5 billion units of plants are sold globally each year. Statisctis show half die within their first year after purchase.

The footprint of a single small indoor potted plant (a 1–2 litre pot) is far from negligible. On average, it represents 1–2 kg of CO₂e emissions - roughly the equivalent of driving a small petrol car for 10 kilometres or running a microwave for over an hour. Water use is equally sobering, comparable to a 15-minute shower or running a dishwasher more than ten times.

Scale that across the 5.5 billion potted plants produced each year globally, and the industry’s emissions rival those of a medium-sized European city or of more than a million cars on the road. Crucially, much of this impact is avoidable. Plants do not fail because they are disposable; they fail because we are rarely taught how to care for them. Educating on how to care for plants is part of our mission.

Once I understood this, I could not unsee it. I realised I had to rethink my business. I was doing well, but I could do far better.

Chapter Four: Change Does Not Happen Overnight

I used to say, I can’t change the world, before understanding that the world does not need changing. Nature functions perfectly well without us. The truth is simpler and harder: I can’t change humanity. But I can choose my battles. Pollution (air, ocean and land), waste, climate change, habitat loss, hunger, and malnutrition are all man-made.

These problems were not created by Mother Nature. They are not natural problems. They are ours. We created them. Responsibility is not optional.

So I shifted my focus. I may not influence humanity, but I can influence my ecosystem: my team, my clients, my community, and everyone who follows my work. I chose to lead by example, by showing what I do, how I do, why it matters, and what it changes. I started shaking things up in my home, in my business, and anything which was not sustainable had to be revisited. This required many approaches, raised many questions and gave me some homework to do. It was not easy.

In a world where everything is based on extraction and polluting, sustainability requires multitasking. It is so easy to destroy or pollute.

The word environment is often treated as something abstract, distant, or external. In reality, its meaning is far more intimate. Derived from the Old French environer, “to surround" and environ, meaning “round about”, the term originally described something which encircles us. When it entered the English language in the early 17th century, it referred simply to being surrounded. Over time, its meaning evolved. By the 19th century, it described the conditions in which life exists, and by the mid-20th century, it had taken on a distinctly ecological meaning.

Today, the environment is often spoken of as something separate from us - yet its origin reminds us of the opposite: everything around us, above us, below us, and within us is environment. We are not outside it nor above it. We are inside it, and responsible for it.

The environment is not an abstract concept. The environment is the soil, the water, the air, the microorganisms, the animals, and it is us as well. Whether we like it or not, our actions ripple through this system. Accountability is a duty.

Change did not happen overnight. I audited my business ruthlessly, starting with waste. Plastic became impossible to ignore. As the business grew, so did its responsibility. I researched suppliers, replaced single-use plastics, refined recycling practices, eliminated synthetic inputs where possible, and chose materials that could genuinely return to Nature. Reducing my impact individually and as a company became part of my mission.

Chapter Five: The Undigestible Truth

Nature cannot process synthetic materials - it is unnatural. If something does not belong to a natural cycle, it will never integrate into one. This principle, often referred to as The Law of Return, which we studied earlier in school, became foundational for me. If a product cannot return to Nature in some form, I avoid it.

Sustainability is not a label; it is a system. If something cannot return to it, it does not belong in it, then it is not sustainable.

Once I scrutinised so-called “eco-products”, the cracks appeared quickly. “Biodegradable” often means plastic with additives, not plant-based or truly circular. Green language sells comfort; it does not guarantee integrity. I had to become meticulous. I curated suppliers based on transparency, material honesty, and genuine environmental commitment.

What we are doing today - how much we consume and how fast we discard versus what we give back, simply put, is not sustainable!

We should shift towards doing more of: buying less, using less, wasting less. This is the simplest and most immediate strategy available to all of us. The benefits may not be immediate, but they matter.

Sustainability is not about optimism; it is about responsibility for what comes next.

Chapter Six: Show Me Who Your Friends Are, and I Will Tell You Who You Are

Over time, I found myself surrounded by like-minded businesses where Nature’s well-being mattered more than growth metrics. Profit remained important, but it was no longer the driver. My business entered a detox phase: reducing pollution, embracing circularity, replacing extraction with restoration. I had to force myself to be very selective with the brands I shop from and where my money is going. I won't support brands that destroy our planet, let alone fund them by buying from them.

There is still much to improve. Sustainability is a process, not a finish line. I will make mistakes. But the intention is unwavering.

If there is one thing I hope for, it is that this same discomfort - the sustainability “bug” - catches you too, until plastic feels wrong, waste feels unacceptable, and better choices become instinctive. If compostable or plant-based options are unavailable, choose recycled. Exhaust every alternative before single-use plastics.

The product shortlist I share next is based on my real use, at home and in my business. This is not sponsored content. I am not an ambassador. These are informed, independent choices. This is unbiased content.

Sustainability is not wellness. It is not self-care. It is accountability. Stewardship. Responsibility. It is not romantic, but it determines how well we live, and whether future generations get the chance to live at all.

Next, I will share a curated list of sustainable alternatives for office and home use in 2026. Each product is assessed for materials, lifecycle, end-of-life, packaging, price, and integrity - calling out greenwashing where it exists.

Because only informed, honest choices sustain life. Everything else quietly erodes it. A sustainable life is a love letter to Mother Nature.

Thank you for your time and attention. It means you care.

By Lucas Cruz Bueno

My Sustainable Product Shortlist for 2026

(Click on the left arrow to expand the view of each product)

Liquid Black Soap (Castalia) by Jabones Beltrán

The Problem: In general, heavy-duty cleaning products contain aggressive chemical formulations, often including strong alkalis (such as sodium hydroxide), acids (including phosphoric, hydrochloric, and sulfamic acids), organic solvents (for example glycol ethers and alcohols), high-strength surfactant systems, chelating agents (such as EDTA and phosphonates), and biocides or disinfectants designed to dissolve grease, remove stubborn dirt, and sanitise surfaces.

These formulations are associated with significantly higher environmental risk, including increased aquatic toxicity and severe disruption of microbial systems that underpin wastewater treatment and natural ecosystems. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified this problem, creating a structural overuse of disinfectants, particularly outside healthcare settings - a pattern of use that has yet to meaningfully decline.

Many of these chemicals persist long enough to cause harm beyond their point of use. In addition to contaminating water systems and degrading aquatic ecosystems, some compounds facilitate the mobilisation and accumulation of heavy metals in soils, ultimately entering the food chain through agricultural uptake.

Market data indicate that globally, approximately 45 million tonnes of industrial cleaning chemicals are produced each year, packaged in an estimated 2.5 million tonnes of plastic. The global recycling rate for this packaging is below 10%. Disposal pathways are heavily skewed towards destruction rather than recovery: around 50% is incinerated, often intentionally, as recycling contaminated industrial containers is technically complex, risky, and costly for governments. 10% is sent to landfill, 10% is classified as “environmental leakage”, and only around 10% is properly cleaned and eventually recycled.

A major but under-acknowledged issue is formulation inefficiency. Depending on the product type and brand, many heavy-duty cleaners are still composed primarily of water:

Ready-to-use products: 90–98% water, 2–10% active ingredients

Semi-concentrates: 70–85% water, 15–30% active ingredients

Concentrates: 30–60% water, 40–70% active ingredients

Ultra-concentrates: 5–25% water, 75–95% active ingredients

This means that intensively, large volumes of water are transported, packaged, and disposed of as product, driving unnecessary emissions, plastic waste, and chemical loading. The issue is not cleaning itself, but a design and procurement system that normalises dilution, disposability, and chemical excess at scale.

Heavy-duty cleaners sit at the high-impact end of the cleaning spectrum. They are used in factories, hospitals, commercial kitchens, transport hubs, warehouses, and large office buildings, often daily and in substantial volumes. Unlike household cleaners, these products combine greater chemical potency, larger container sizes, and institutional disposal routes, which, together, amplify their environmental footprint.

As a business, this was one of the very first sustainable swaps I made, and years later, I still love it. I use it constantly. Quietly, it changed how I think about cleaning. Liquid black soap, also known as "potassium soap", is one of the oldest and lowest-impact cleaning agents still in use. The Castalia Black Soap stands out because it is chemically simple, biodegradable by design, and remarkably versatile. One product replaces an entire shelf of synthetic heavy-duty cleaners, without pretending to be anything it is not. You can find this product available in our online shop via this link.

There is nothing glamorous about it. No fragrances, no colourful bottles, no performance theatre. Made from vegetable oils transformed into soap, it contains no petrochemical surfactants or synthetic additives. It cleans because chemistry works, not because marketing says so. Founded in 1922, Jabones Beltrán is a Spanish family-run soap maker whose sustainability is process-driven rather than trend-led. The Castalia line reflects that ethos: functional, ecological, and uncompromising.

This is not a spray-and-forget cleaner. It arrives concentrated and requires dilution and intention, an adjustment that feels more like a feature than a flaw. It cleans thoroughly but does not disinfect, which is often more than sufficient for everyday use. The only real downside is the plastic bottle. While recyclable, a recycled-plastic option would be a natural next step for this brand I love.

At €4.00–€6.00 for a 250 ml concentrate, diluted at roughly 1:20, it costs around €0.80–€1.00 per litre of usable cleaner. You can play with the concentrations depending on the necessity, but when compared to an average of €4.50 per

litre for conventional alternatives, cleaning sustainably was never so cheap. The Castalia Black Soap is unflashy. Honest. Incredibly effective. Once you understand it, you stop looking for anything else. It literally changed my cleaning-life forever.

Refillable Cleaning Concentrates (EcoDrops) by Ocean Saver

The Problem: Surface cleaners are marketed as light, everyday products. Yet from an environmental perspective, they are among the most structurally inefficient and chemically diffuse cleaning products in circulation. They are high-frequency, low-dose, and high-turnover items. Globally, tens of billions of spray bottles are sold every year. Most are replaced long before the packaging itself wears out, and many households own multiple overlapping products that perform essentially the same function. This is not innovation; it is marketing-driven redundancy, and it is remarkably effective.

The result is continuous packaging and chemical leaching, not a one-off impact. A typical spray cleaner formulation consists of 90–98% water and only 2–10% active ingredients, making surface sprays one of the worst plastic-to-function ratios in the cleaning category. A critical and often overlooked issue lies in the spray trigger mechanism, which represents a quiet but persistent plastic design failure.

Consequently, around 30% of spray cleaner packaging ends up in landfill, 45% is incinerated, and 10% is classified as “environmental leakage”, leaving only around 20% potentially recycled - and only if consumers thoroughly rinse the container and separate the bottle from the trigger before disposal. Beyond packaging, spray cleaners represent an inefficient chemical delivery system built on chronic, diffuse, and cumulative release of residues into wastewater systems. Over time, this contributes to long-term aquatic pollution, degrading water quality and placing additional stress on already burdened ecosystems. This is not a convenience problem, it is a design and consumption system failure.

This is one of my favourite sustainable cleaning alternatives, and brand, for a wide range of good reasons. Ocean Saver tackles one of the most overlooked sources of waste in cleaning: single-use plastic bottles filled mostly with water. Conventional sprays sell you plastic, transport emissions, and dilution. Ocean Saver removes the inefficiency entirely. Their EcoDrops are ultra-concentrated dry capsules that dissolve in tap water, which you already have at home or in the office.

By eliminating liquid transport, the brand dramatically reduces plastic use, shipping emissions, and storage volume. This is source reduction, not downstream recycling, and that distinction matters. The only trade-off is a small behavioural shift. You need to reuse an existing bottle and mix the product yourself. For first-time users, this may feel less convenient, but the adjustment is minimal and quickly becomes second nature.

Performance-wise, the Multi-Purpose surfaces and Glass Cleaner EcoDrops cover the vast majority of everyday cleaning needs. Price-wise, they are equally compelling: each EcoDrop costs approximately €1.90–€2.50 and makes 750 ml to 1 litre of cleaner, working out to around €2.00–€2.50 per litre. Conventional ready-to-use sprays average around €3.90 per litre, often using heavier plastic packaging and weaker sustainability profiles. Ditching brands like Cif or Ajax is an easy decision here.

Material and end-of-life choices are well thought out. The concentrates are dry, packaged in cardboard (widely recyclable) and formulated with plant-based, biodegradable surfactants. Plastic is avoided at the point of purchase altogether by relying on bottle reuse. Beyond surface cleaners, Ocean Saver’s range extends into dishwashing and laundry, applying the same low-waste logic across categories. Simple, effective, and genuinely disruptive.

Ocean Saver proves that effective cleaning does not need to come wrapped in plastic and water. As a loyal consumer, my only suggestion would be to take the final step by using recycled cardboard for their paper packaging and printing with plant-based inks, such as hydro-soy or water-based alternatives. Given how information-rich the packaging is, this shift would meaningfully reduce its environmental footprint. At that point, the brand’s ocean-first narrative would feel fully realised, designed so that every component is as harmless as possible, even at the end of life inside and out.

Biodegradable Dishwashing Solid Bar (Biobel) by Jabones Beltrán

The Problem: Dishwashing liquid is one of the most frequently purchased household cleaning products. It feels indispensable, benign, and even responsible yet structurally it mirrors the same environmental failures seen in floor cleaners, often more intensely due to higher turnover and daily use. Globally, billions of bottles of dishwashing liquid are sold each year, often with multiple purchases per household annually. Because bottles are emptied quickly, plastic throughput remains constant, even in “eco-conscious” homes.

A typical liquid dish soap formulation contains approximately 90% water and 10% active ingredients. This creates two major environmental inefficiencies. First, it generates unnecessary transport emissions, effectively turning tap water into a globally traded product. Second, it results in severe packaging inefficiency: each bottle contains very little functional chemistry - often 10% or less in effective surfactants - yet large volumes of plastic are used to deliver minimal cleaning power. This produces one of the worst plastic-to-function ratios in the household products category. This is fundamentally a design problem, not a hygiene requirement.

Actual recycling rates for cleaning product bottles are significantly lower than headline statistics suggest. Containers are frequently contaminated with detergent residue, pumps and caps are rarely recycled, and the use of coloured plastics further reduces recyclability. In use, dishwashing liquid is combined with hot water and grease, increasing chemical mobilisation and leading to direct discharge into wastewater systems.

Dishwashing liquid pollution is not a spill problem; it is a background load problem. Although regulations exist to control the toxicity of cleaning agents, many surfactants and additives persist long enough to remain biologically active in water before they fully break down. The same surface-tension–altering properties that allow detergents to remove grease and food residues also interfere with aquatic life. In natural systems, these compounds can disrupt cell membranes, reduce reproductive success, alter feed and hunting behaviour, and interfere with gas exchange at the water surface, affecting organisms with permeable skin or gills.

Over time, this continuous exposure weakens populations, reduces ecosystem resilience, and compounds other environmental stressors such as global warming, nutrient runoff, and pharmaceutical contamination. Even surfactants considered “short-lived” can cause harm when inputs are constant and widespread, as they are in urban wastewater systems. The issue, therefore, is not acute toxicity, but chronic, cumulative exposure driven by everyday use.

I used to find it genuinely frustrating to buy dishwashing liquid every month, knowing that even biodegradable formulas still come wrapped in single-use plastic. Biobel’s solid dishwashing bar completely changed that equation and took a massive weight off my conscience. Once you go Biobel, you can't go back.

Solid dishwashing bars are one of the most effective plastic-elimination swaps in any kitchen or office pantry. Probably the fastest, cheapest, yet the best decision you can make today. Biobel’s version stands out by combining a certified ecological formulation, minimal ingredients, and zero liquid transport, while still delivering excellent degreasing performance. The only real adjustment is behavioural: it requires a brush or sponge and a slightly different approach to dosing compared to liquid detergents. I keep mine in a soap tray.

Biobel is the certified ecological cleaning line of Jabones Beltrán, a Spanish family-owned soap maker founded in 1922. The bar is made from 100% ingredients of natural origin, certified by ECOCERT, and formulated with vegetable-based surfactants. It contains no synthetic fragrances, dyes, phosphates, or petrochemical surfactants. Approximately 25% of the total ingredients are from organic farming. This is formulation-led sustainability, fully biodegradable by design, without decorative green claims.

From a cost perspective, the numbers are compelling. A 150g bar typically retails between €3.50 and €4.50 and replaces roughly two to three bottles of liquid dish soap (500–750 ml each). That equates to an estimated €1.50–€2.25 per litre of liquid equivalent. By comparison, mainstream dishwashing liquids in Portugal often cost €3.80–€5.40 per litre. The solid bar is therefore price-competitive or cheaper per wash. You can find this product available in our online shop via this link.

Beyond cost, the environmental gains are clear: no plastic bottles, no water transport, and no recurring packaging waste. The only care required is keeping the bar dry between uses to maximise longevity. I use this bar multiple times a day, every day. It is efficient, very generous, long-lasting, and quietly reassuring - proof that effective cleaning does not need plastic, excess water, or compromising ethics.

Biobel´s home cleaning line expands to a wide variety of other products; my only wish is that they would ditch all plastic packaging and choose recycled paper or plastic alternatives only, or make everything that is liquid concentrated.

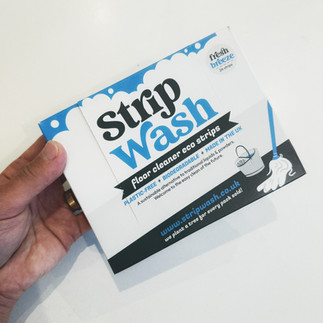

Biodegradable Floor Cleaning Strips (Strip Wash) by EcoLiving

The Problem: Floor cleaners sit in a blind spot of environmental scrutiny. They combine three of the most problematic elements of modern consumption: single-use plastic packaging, water-heavy formulations, and routine overuse. Floor cleaners are a repeat-purchase category, with billions of litres sold each year globally, almost entirely packaged in single-use plastic bottles.

The defining feature of conventional floor cleaners is that they consist of roughly 85–95% water. This has two major consequences. First, it generates unnecessary transport emissions, effectively turning tap water into a globally traded product. Second, it creates severe packaging inefficiency: each bottle contains very little functional chemistry (5% or less of the active ingredients), yet large volumes of plastic are used to deliver minimal cleaning power. This results in one of the worst plastic-to-function ratios in the household products category.

Compounding this issue, floor cleaners are diluted with water during use and then disposed of directly into wastewater systems. Some chemical components persist through treatment processes and ultimately enter rivers, sediments, and agricultural soils (via sewage sludge), where they can accumulate and move through the food chain that we then consume. This is not a single, catastrophic pollution event, but rather a form of chronic, continuous, and cumulative environmental exposure.

The biggest sustainability improvements in floor cleaning do not come from swapping one liquid for another. They come from changing the delivery system, and that is exactly why Strip should be the way forward.

Strip Wash challenges this model by replacing liquid cleaners with ultra-light, biodegradable cleaning strips that dissolve in water, dramatically reducing plastic use, transport emissions, and storage volume. The trade-off is behavioural. Instead of pouring liquid, you dissolve a strip, and the fragrance intensity is subtler than conventional products. Performance depends on correct dilution and warm water.

Strip Wash operates on a simple, systemic sustainability logic: remove water, remove plastic, reduce logistics. The strips are manufactured in the UK, packaged entirely in cardboard, and fully recyclable. Given that roughly 90% of conventional cleaning products are water, Strip Wash focuses on delivering only the active product in sheet form, eliminating unnecessary transport of liquid. Usage is straightforward: dissolve one strip in 3–5 litres of warm water, stir, then mop as usual.

A box contains 24 strips and typically retails for €8.00, resulting in a cost per clean of approximately €0.33. At first glance, this appears more expensive than conventional alternatives. Standard floor cleaners in Portugal retail at €2.50–€3.50 per bottle and yield around 20 to 25 washes, roughly €0.12 to €0.18 per clean. However, this comparison is misleading.

Conventional cleaners are typically 60–90% water, meaning the actual non-water cleaning formula accounts for only 10–40% of the product. When recalculating cost per clean based on active, non-water content, conventional products effectively cost around €1.10–€1.60 per clean. On that basis, Strip Wash becomes one of the most cost-efficient options available. This “exclude-water” framing is not a perfect chemistry comparison because formulas also contain binders, salts, and fragrances, but it is a far more honest way to assess value in a category dominated by dilution. Doing that would be to the disadvantage of disadvantage to this product.

Beyond product design, Strip Wash - produced by EcoLiving - operates as a carbon-neutral brand and supports reforestation through the Eden Reforestation Projects, combining emissions reduction with social impact. Choosing Strip Wash means I plant trees as a mop my floors, how great is this!?

The same logic extends across their range, including laundry strips - which I use too - following the same low-waste, high-efficiency model. Strip Wash is not just a different format - it is a structural rethink of how cleaning products should exist. In fact, so many products could just be produced like that: compacted, concentrated, and easy because we don't need to be sold water.

Compostable Waste Bin Bags (Bag By Nature) by BIOvative

The Problem: The Planet's true nightmare! Bin bags are unique among disposable plastics in that they have absolutely zero service life: they are manufactured explicitly to become waste, and then used solely to contain other waste. This makes them one of the highest-volume, lowest-recovery plastic products in circulation. Global production is estimated at around 1.3 trillion bin bags per year, corresponding to approximately 12 million tonnes of plastic annually. Of this, 65% ends up in landfill, 25% is incinerated, and 8% becomes “environmental leakage”, escaping formal waste systems.

Discussion of recyclability for bin liners is effectively meaningless. Although polyethene is recyclable in theory, less than 2% of bin bags are recycled globally, and in many regions the practical recycling rate is zero. Bin bags are unsuitable for recycling because they become contaminated with mixed waste, are too thin for sorting machinery, and frequently jam recycling equipment. As a result, municipal systems explicitly reject them. Compounding this, poor household waste separation means bin liners are almost always tied to mixed waste streams, eliminating any realistic end-of-life recycling potential.

Here is the unsettling part: plastic bin bags emerged in the early to mid-1950s. Almost every bin bag ever produced still exists, either intact or fragmented. Over the past 71 years, an estimated 95 trillion bin bags have been manufactured. In comparison with total global plastic production since the 1950s - approximately 10 billion tonnes - bin bags alone account for around 15% of all plastic ever produced. Realistically, around 1.3 billion tonnes (98%) of bin-bag plastic remains in the environment or within waste systems today. That equates to roughly:

100,000 Eiffel Towers’ worth of plastic, by weight

More plastic than all commercial aircraft ever built combined

Enough plastic to wrap the Earth in film dozens of times

Switching to BIOvative made me sleep at night again. Plastic gave me nightmares. Bin bags are a high-volume, low-attention consumable used daily, discarded immediately, and almost always made of plastic. Biovative’s Bag by Nature compostable bin bags stand out because they replace conventional polyethene liners with certified compostable materials specifically designed for organic waste. This is one of the few cases where compostability genuinely makes sense: the bag and its contents can enter the same waste stream.

Biovative is a small, family-owned German manufacturer founded by Janine and Uwe, specialising in compostable packaging and waste-management solutions made from renewable raw materials. The brand focuses on certified, use-case-appropriate applications rather than generic “biodegradable” plastics - an approach that is consistent, transparent, and free from greenwashing.

The bags are made from GMO-free, plant-based biopolymers derived from starch, sugar, vegetable oils, and a controlled share of fossil-based inputs required for performance. Unlike many compostable products intended only for industrial composting, these bags are specifically designed for organic residential waste collection and are compatible with municipal bio-waste systems. When disposed of correctly, they break down in under six weeks. In my own compost heap, the decomposition process can be seen in just a few days. Slugs, ants, worms love it!

The trade-offs are cost and durability. These bags are engineered to decompose, not to last indefinitely. Pricing reflects that reality: small bio-waste bags (10-30 litres) cost between €0.20 - €0.46 per unit, medium kitchen bags (120 litres) €0.91, and large bins (240 litres) €1.25 per bag - roughly 2–3× more expensive than conventional plastic liners. This is where behaviour change and mind refocusing matter.

Switching to compostable bin bags works best alongside better waste separation, reduced consumption, and lower overall waste volumes. In my own experience, improving recycling habits significantly reduced both waste output and bag usage over time. Ther lesser the rubbish I accumulate, the fewer bags I need. The frequency of throwing your trash also impacts volume per unit. I use one small bag per week for my food scraps (that goes directly to my compost) x4-5 weeks means between €1.20-€1.50 per month. One roll can last me up to 12 months! It is not because of €1.50 per month that I will destroy the oceans, skies and land!

Environmentally, the benefit is conditional on correct disposal, but when used as intended, these bags solve a real problem: plastic contamination in organic waste streams. Instead of waiting 500 to 1000 years and resulting in microplastics entering to the food system and back to human, animal and soil health, they get the job done in 6 weeks (or less). For kitchens, offices, and buildings that separate bio-waste, they are not just a sustainable alternative; they are often the only responsible option.

Biovative’s commitment extends beyond product design. Since 2020, the company has supported the Support A Local initiative run by Corinna, providing food and drinking water to families in Indonesia while avoiding additional plastic waste in regions with limited waste management infrastructure. Often, our developed countries dump all our trash in their backyard. Using BIOvative bio-bags will never happen. The bag will be gone in a matter of weeks, even before it reaches the shore. Choosing Biovative supports waste reduction, community resilience, and tangible environmental action where it is most needed. One bio-waste bag has many positive repercussions. A practical, honest solution designed for the system it serves.

Biodegradable Cling Film (Bio Food Wrap) by Eco Green Living

The Problem: Knowing this can feel nightmarish. Most conventional cling film is made from LDPE (low-density polyethylene) or PVC (polyvinyl chloride) - both fossil fuel–derived, non-biodegradable plastics engineered to be flexible, stretchable, and adhesive. These same properties make cling film convenient in use, but also render it effectively unrecyclable and highly prone to fragmentation into microplastics.

Globally, billions of rolls are produced each year, yet recyclability - 0% - is largely irrelevant in practice. Cling film is too thin for sorting machinery, readily tangles recycling equipment, and is almost always contaminated with food residues. As a result, municipal recycling systems actively reject soft plastic films. Of the estimated 80 million tonnes of plastic film produced annually, around 4% is used for cling film production. Approximately 70% ends up in landfill, where it degrades into trillions of microplastic particles, while the remaining 30% is incinerated.

Cling film is one of the most problematic everyday plastics - probably the worst of all: short-lived, rarely recycled, and almost impossible to process in conventional recycling systems due to its thin, flexible structure, which clogs machinery and therefore waste management facilities don't even try - it literally lasts forever in the environment. This makes cling film a high-impact, low-visibility problem in both homes and offices.

Eco Green Living is one of my favourite brands. Based in the UK, the company specialises in sustainable household and catering consumables designed for real-world, high-use environments. Its mission is refreshingly direct: to make sustainable living easy, accessible, and genuinely impactful. Importantly, the brand relies on certification-led claims rather than vague “biodegradable” language.

Eco Green Living’s compostable cling film stands out because it directly replaces conventional PVC or PE film without requiring behaviour change, while offering a certified compostable end-of-life. Whether it ends up in waste streams, processing facilities, or the environment, compostability addresses a failure point where recycling simply does not work.

The material is made from plant-based biopolymers, is explicitly PE-free and PVC-free, and is designed to break down into non-toxic components under industrial composting conditions. But what does this mean for me consumer? For any biodegradable product to be considered good for industrial composting, the compliant product must: biodegrade (8 to 12 weeks), disintegrate physically into fragments <2 mm, so no visible residues remain in compost, and leave no toxic residues behind. After, compost must pass ecotoxicity and heavy metal limits to be eligible to support plant growth, germination or biomass production.

Packaging is kept simple with a cardboard outer sleeve. In my view, a clearer explanation of domestic composting standards and disposal guidelines is needed, and it would further strengthen their transparency, particularly for end users navigating compostability claims and trying to translate regulations into simple terms.

The trade-offs are cost. A typical 30 m roll retails at around €6.50, translating to approximately €0.21 per metre. By comparison, conventional cling film averages around €3.00 per roll, or €0.10 per metre. This makes the compostable option roughly 2.5–3× more expensive, but the premium price tag reflects certified compostability and responsible material choice, not branding. You can find this product available in our online shop via this link.

Eco Green Living also backs its products with wider environmental action. The company partners with Ecologi to plant trees. With every order, they plant one tree on your behalf and support TreeSisters, contributing to reforestation projects that benefit both ecosystems and local communities, particularly women. In addition, a portion of each order supports vetted carbon removal initiatives through organisations such as Heirloom, Remora, and Charm, with oversight from Carbon Direct.

So, are you saying when I choose Eco Green Living, I effectively buy a product, plus I indirectly make donations to two NGOs and support three carbon removal initiatives all in the same transaction? Yes, that is right! It buys you time doing the right thing. This is a clear case where sustainability is an investment in the future. Given the persistent pollution caused by PE and PVC films, choosing compostable alternatives and supporting brands that go beyond product-level responsibility makes both environmental and ethical sense.

Organic Compostable Disposable Gloves by Plantvibes

The Problem: Driven largely by the healthcare and food sectors, global production of nitrile, vinyl, and latex disposable gloves is estimated to reach around 400 billion units per year. Due to potential contamination from biological material and cleaning chemicals, no municipal recycling streams exist for these products. As a result, approximately 60% end up in landfill, where they contribute to soil and water contamination; 30% are incinerated, releasing polluting gases that are significant contributors to climate change; and the remaining 10% are classified as “environmental leakage”, meaning their final destination is difficult to track.

During disposal and degradation, gloves shed microplastic particles through abrasion and weathering, which enter wastewater systems, soils, and ultimately accumulate within indoor environments as household dust. While disposable gloves are increasingly incinerated, reusable gloves are predominantly sent to landfill, further underscoring the lack of circular end-of-life solutions for protective handwear. Whichever one we were using, this must stop!

Plantvibes was founded by Andrei after witnessing first-hand the scale of plastic pollution in Southeast Asia. That experience shaped him and his brand’s mission: to develop CO₂-neutral, ocean-conscious products made from renewable raw materials rather than fossil plastics.

The Plantvibes disposable gloves replace conventional nitrile with plant-based bioplastics, using a PLA and starch-derived polymer blend rather than petroleum-based plastic. Marketed as compostable and derived from renewable resources, they offer a reduced fossil-plastic footprint. They are best suited for light-duty, short-duration tasks. We use them intensively - for soil work, insect or fungal treatments - where they outperform conventional gardening gloves by preserving tactile sensitivity.

Precision matters. Like most compostable gloves, their environmental benefit depends on access to appropriate composting infrastructure. They are not designed for heavy cleaning or chemical handling, and their sustainability only holds if disposal conditions are correct. A key limitation is transparency. While the product page uses the term “100% kompostierbar”, it does not clarify: which compostability standard applies, whether the gloves are suitable for home or industrial composting or the conditions and timeframe required for breakdown. This needs improvement.

Plantvibes clearly aims to reduce plastic waste and promote plant-based alternatives, and references CO₂ neutrality through lifecycle offsets. However, without explicit certification details, compostability remains an assertion rather than a verifiable claim. For consumers, this lack of clarity makes end-of-life handling uncertain and weakens trust. I run my own tests but, but this is not my job.

Conceptually strong and materially preferable to nitrile, these gloves represent a meaningful step toward lower-impact disposables. Clearer certification and disposal guidance would significantly strengthen their environmental credibility and the confidence to continue investing in them.

Eco Rubber Gloves and Loofah Sponges by Seep

The Problem: In general, non-sustainable cleaning gloves pose a significant and largely overlooked environmental problem. Approximately 5 billion cleaning gloves are produced each year, yet less than 1% are recycled. This is primarily due to their mixed-material composition, contamination from cleaning chemicals - often rejected by municipal recycling systems - and the fact that industrial recycling programmes exist only at pilot scale. As a result, around 70% end up in landfill, 25% are incinerated, and the fate of the remaining 4% remains unknown.

Reusable natural rubber gloves represent a less harmful alternative; however, they are still rarely recycled and therefore only partially address the problem.

Kitchen sponges, however, are arguably an even larger and more invisible issue. With an average replacement rate of every 2–4 weeks, global production is estimated to reach 45 billion kitchen sponges per year. Due to their composite construction (foam, abrasives, and adhesives), heavy contamination with food waste, and the absence of viable recycling infrastructure, recycling is effectively non-existent. Approximately 80% are sent to landfill, 15% are incinerated, and 5% are classified as “environmental leakage”. Kitchen sponges are among the least recyclable consumer products in existence, and this is a problem that demands immediate change.

Seep’s eco rubber gloves are one of the strongest low-impact options available for heavy-duty cleaning that I have used so far. Made from natural rubber latex sourced from rubber trees, they are fully plastic-free and designed for long-term reuse. Unlike nitrile or bioplastic gloves, natural rubber is not a plastic polymer - it is a plant-derived elastomer processed without petroleum feedstocks. In practical terms, this means no microplastics are released through wear and tear, and no reliance on biodegradation additives.

The latex is harvested through rubber tapping, a process that does not harm the trees. The gloves are certified biodegradable under ASTM D5511, a standard typically associated with anaerobic environments such as landfills. While Seep advises cutting up worn gloves and placing them in general waste to support breakdown, it is important to note that biodegradation will depend on specific disposal conditions rather than occurring rapidly in home compost. Clearer end-of-life guidance would strengthen transparency here.

Packaging and inserts are fully recyclable (though not yet made from recycled paper), and Seep offsets its carbon footprint through a reforestation partnership with the NGO “On A Mission”. Ethically, the brand shows genuine intent beyond product design.

Price-wise, these gloves sit at a premium: a pair costs around €3.90, compared with €2.80–€3.40 for conventional reusable rubber gloves. However, their durability makes them cost-effective over time, and the reduced environmental impact justifies the investment.

Alongside the gloves, Seep’s loofah sponges are powerful performers. Made from plant-based loofah (similar to a pumpkin) and wood pulp cellulose, they are suitable for home composting, last significantly longer than conventional sponges (around 1–2 months), and generate approximately 18% less CO₂ across their lifecycle. I would be delighted to witness the production of these products.

Thoughtful, durable, and materially honest, Seep’s range proves that plastic-free cleaning tools can perform just as well - if not better - than conventional alternatives. When browsing through their online shop, I see no plastic, and this makes me so happy. Definitely a brand you want to know!

Recycled Cleaning Cloth & Fregona Mop (Vita) by Bayeco

The Problem: In general, using non-sustainable alternatives poses a significant environmental challenge, one that remains largely invisible. Microfibre products sit at the intersection of textiles, plastics, and cleaning sectors in which end-of-life regulation is weak or fragmented. According to recent estimates, approximately 25 billion microfibre cleaning cloths and 2.5 billion mop heads are produced globally each year. The most alarming aspect is that less than 1% of microfibre cleaning textiles are recycled. Around 75% end up in landfill, a further 15% are incinerated, leaving only 1% recycled, while the fate of the remaining 9% remains unknown.

The problem is further compounded by the fact that a single microfibre cloth can shed hundreds of thousands to millions of microfibres over its lifetime. Although microfiber is highly effective for cleaning, it represents a largely unregulated source of microplastic pollution. Recycled microfiber reduces virgin plastic use, but it does not eliminate the underlying environmental issue.

Bayeco sits comfortably in the “better mainstream” sustainability tier. These are products that look and perform like conventional household cleaning tools, but with a measurably improved material footprint primarily through the use of recycled PET and certified fibres.

The strength of the Vita range lies in durability. If a plastic bottle can last up to 1000 years to disintegrate, trust me, this mop and cloth will last you many years. Both the multi-purpose cloth and the mop replace disposable or short-lived cleaning tools with washable, long-lasting alternatives made partly from waste plastic. This is not a zero-plastic solution, and Bayeco is transparent about that. Instead, it offers plastic circularity: turning existing plastic waste into functional, reusable products. Hence, it is important to properly dispose of your plastics so companies like Bayeco can take over.

Bayeco communicates its sustainability claims clearly, both on packaging and online, referencing recycled content, eco-efficient solutions, and participation in GRS-aligned supply chains (Global Recycled Standard). The messaging is consistent and avoids exaggerated claims, which is refreshing in this category.

From a pricing perspective, Bayeco is often at price parity or slightly cheaper than premium conventional brands, making the switch an easy decision. Performance is solid, longevity is the goal, and reuse is strongly encouraged.

Material-wise, these products are made from recycled PET bottles. They are not biodegradable, but they are recyclable at end-of-life, ideally through textile waste streams where available.

This hybrid identity - plastic turned fabric - does raise legitimate questions about disposal clarity, as waste systems are not always well equipped to handle such materials or aware of such innovations. That said, the design intent is clear: use them for as long as possible. Wash them, reuse them, and only replace them when functionality genuinely degrades.

Practical, honest, and accessible. Bayeco offers a meaningful step away from disposability, even if it does not pretend to be plastic-free. As one of their clients, I make an appeal for Bayeco to ditch all plastic packaging and replace it with recycled paper, as seen in other products or, or biodegradable plant-based polymer plastic. For some odd reason, Bayeco stopped featuring most of its Vita line on Amazon and almost nothing on its own website. Strange right?

Paper Towels, Toilet Paper & Napkins (Love & Action ) by Renova

The Problem: Disposable paper is one of the most normalised forms of consumption in modern life. The most significant sustainability difference in paper products is not branding or colour, but fibre origin. While consumers understandably favour soft and strong tissue, these qualities are typically achieved through the use of virgin fibres, which offer maximum strength. However, virgin pulp carries substantial upstream impacts, including land-use pressure (with plantations often replacing natural ecosystems), higher water consumption, and more energy- and chemical-intensive processing, particularly during bleaching.

Disposable paper is not a one-off purchase; it is an ongoing extraction contract. From a sustainability perspective, kitchen roll is the most wasteful paper category, where “use once and throw away” has become a default behaviour rather than a functional necessity. It is also the paper category most easily reduced without compromising hygiene.

Toilet paper and kitchen paper are not “minor” consumables. They are repeat purchases by design, with demand driven by routine rather than actual need. The outcome is predictable: continuous demand for forest fibres, ongoing packaging and transport, and a constant stream of short-lived waste. The most effective lever is not identifying the “best” product, but reconsidering what we treat as disposable.

For toilet paper, choose 100% recycled, certified options (such as EU Ecolabel or FSC Recycled). For kitchen use, prioritise washable cloths and minimise reliance on paper towels. Finally, reuse cloth napkins multiple times between washes, until they are no longer hygienically viable.

Disposable paper is not a one-time purchase—it is an ongoing extraction contract. Actions that sound so simple and yet so polluting if not done right. How can I brush my bottom correctly then? Well, if you are in Portugal, you most certainly heard of them. Introducing "The Sexiest Paper On Earth" by Renova.

Renova’s Love & Action range stands out in the mainstream paper category by doing something many competitors still avoid: taking sustainability seriously at scale. The ecological line is made from 100% recycled paper; the products carry both FSC® and EU Ecolabel certification, signalling responsible sourcing, reduced environmental impact, and credible third-party verification. Performance-wise, they deliver exactly what you expect from Renova: soft, strong, and reliable paper supplies.

From a materials perspective, the fundamentals are solid. The ecological line is made of recycled fibres, partially recyclable packaging, and a long-standing environmental policy (public since 1993), placing Renova well ahead of generic supermarket alternatives. The brand’s corporate DNA states commitments to protect ecosystems, use resources responsibly, invest in low-impact technologies, and engage communities. From an educated consumer's point of view, the contradiction lies in the details.

Some of the Love & Action eco products are still wrapped in plastic, but not plant-base one. This feels unnecessary, especially when Renova is a key leader in paper making and already markets paper-wrapped virgin tissue alternatives. For a line positioned as "environmentally conscious", eliminating any plastic would be the obvious final step. This would solidify their mission and close any loopholes in their green narrative. Knowing how polluting virgin fibres are, they should strongly consider keeping everything 100% recycled. They add no value there. Their strong suit is really making great recycled alternatives.

Price is the other trade-off. At approximately €2.08–€3.16 per kitchen roll, Love & Action eco line sits above basic unbranded towels, though still within the broader market average (around €3.06 per roll). You are paying for recycled content and certification, and that is a reasonable exchange.

For a brand that proudly calls itself “The Sexiest Paper on Earth”, going fully plastic-free would turn good sustainability into leadership. Until then, Love & Action is a strong, credible option, but one still holding back from its full potential. Other equivalent brands are going full eco with content and packaging, but they are not local, so given the amount of paper we need, buying weekly or monthly from the UK or other non-EU countries makes the purchasing unsustainably expensive and defeats the purpose of sustainability. I would love to see Renova's sustainability credibility expand and validate that they are the right choice for my home and business. I would also love to visit their factory and tell the story of this local, well-intentioned Portuguese brand.

Biodegradable and Compostable Gourmet Bio Coffee Capsules by Bicafé

The Problem: Plastic and aluminium coffee capsules are a textbook example of high-impact, low-utility packaging. They combine three of the most problematic features of modern consumption: single-serve convenience, composite materials, and disposability normalised at scale.

Globally, an estimated 65 billion coffee capsules are produced every year. By weight, this equates to over 100,000 tonnes of aluminium and plastic annually, excluding secondary packaging such as boxes, sleeves, and transport materials. This multi-material construction, combined with organic contamination from coffee grounds, renders capsules structurally incompatible with standard municipal recycling systems. In theory, aluminium is highly recyclable; in practice, capsule design prevents effective recovery.

Claims of “recyclable plastic” are frequently theoretical, relying on industrial processes that do not exist at a meaningful scale. Despite aggressive branding claims, real-world outcomes are stark. Less than 20% of coffee capsules are recycled globally. Around 40% end up in landfill, where aluminium never degrades and plastics fragment into microplastics. A further 25% are incinerated, often intentionally due to contamination and sorting costs, while the remaining 15% are classified as environmental leakage, entering informal waste streams, litter pathways, or export routes with inadequate handling standards.

Coffee capsules are not an accidental waste problem; they are a designed waste system. The environmental cost is not driven by coffee consumption itself, but by single-use delivery formats engineered for convenience rather than recovery. This is not a failure of consumer recycling behaviour. It is a failure of product design, material choices, and regulatory tolerance. Brands that promote this product should be held accountable.

As a coffee lover, every espresso used to come with a "bitter" aftertaste. The bitterness came from knowing each sip meant an aluminium capsule, more plastic, and complex recycling that rarely happens. Discovering Bicafé’s compostable capsules changed that entirely. At home and in the office, coffee now tastes better knowing the planet is not paying the price and that I can do my share by disposing of it properly and adding to my compost heap.

Single-serve coffee capsules are among the most waste-intensive everyday products, largely due to aluminium and plastic composites that require specialised recycling systems. Bicafé’s biodegradable capsules stand out by removing aluminium and fossil plastic altogether, replacing them with certified compostable PLA capsules designed to enter the organic waste stream.

Bicafé is a Portuguese coffee roaster with over 60 years of history. In recent years, the company has invested heavily in lower-impact production, compostable capsule technology, and renewable energy. The capsules are made from PLA derived from fermented plant starches coming from beets, corn, and cassava, and are certified biodegradable and compostable – a genuine aluminium-free and plastic-free capsule option. The coffee content also adds value to the entire composting process, giving organic matter as fuel for microorganisms.

Under proper composting conditions, the capsules break down in approximately 12 weeks. Cardboard outer packaging is recyclable, and production is powered by on-site solar energy with over 960 photovoltaic panels that generate more than 120% of the factory’s electricity needs, avoiding over 300 tonnes of CO₂ emissions annually.

This is material substitution, not recycling offsets. Correct disposal is essential. These capsules should go into organic waste, not plastic recycling. When used as intended, they represent one of the most credible compostable applications in the coffee sector.

Price-wise, Bicafé is highly competitive. A pack of 10 capsules typically retails between €2.69 and €3.19 (€0.27–€0.32 per capsule). By comparison, Nespresso aluminium capsules average around €0.52 per cup, while supermarket and third-party brands range from €0.35–€0.45. Bicafé offers better environmental performance at a lower or comparable price without relying on specialised recycling schemes that most consumers do not follow anyway.

Walking down the coffee aisle, the dominance of polluting aluminium capsules is staggering, with compostable options confined to a small corner. Bicafé proves that another model is not only possible but viable. From a consumer and environmental perspective, my only frustration is this: why does a brand capable of leading such meaningful change still produce plastic capsules as part of their coffee collection?

Bicafé’s plastic capsules are genuinely disruptive and counterbalance, negatively, all the sustainable efforts and renewable energy mission. We want Bicafé to be fully committed to biodegradable and compostable capsules - only and full stop! This would not just reduce impact, it could redefine capsule coffee in Portugal. For capsule drinkers looking for the lowest-impact capsule option available today, this is it. Bicafé needs to redefine its priorities and ditch plastic all together and become Portugal´s first 100% sustainable coffee brand and lead the market by example.

Wet Toilet Tissues by El Corte Inglés

The Problem: This is one of the most environmentally problematic “everyday” product categories. Global production of so-called “flushable” wipes - including baby and adult wipes - is estimated to produce approximately 600 billion units per year. Despite their branding, most wipes are plastic-based. Due to their mixed fibre composition, contamination with human waste, and immediate disposal after use, no viable recycling streams exist. As a result, around 65% end up in landfill, 20% enter sewer systems, and 15% are incinerated.

Beyond the environmental burden, flushing wipes down the toilet creates widespread infrastructure damage. Wipes are responsible for approximately 93% of sewer blockages, contributing to the formation of fatbergs - solid masses of wipes combined with fats and oils - and the failure of pumping systems, costing millions of euros annually in municipal repairs. Wipes are also among the largest contributors to microfibre pollution by unit count, shedding microplastic fibres immediately upon contact with moisture and releasing them directly into aquatic environments.

El Corte Inglés is a major Iberian retailer, yet eco-conscious options within its grocery range remain limited. This wet toilet tissue does the job at a very low price, making it an accessible everyday product, but its sustainability credentials are unclear.

The wipes are described as being made from “100% natural fibres”, a vague claim without supporting details of their real composition, which can be a series of raw materials like cotton, bamboo, or wooden fibres. There is very little information given apart from an FSC® certification, signalling responsible sourcing, reduced environmental impact, and credible third-party verification. However, no clear guidance on sourcing or end-of-life disposal.

As consumers, all we have to hold on to is one single word - biodegradable -, but it is not enough, and they must improve on this. Any “biodegradable” reference is unsubstantiated, making environmental impact difficult to assess in the long run. You can have plastics with biodegradation additives that help plastic degrade in less than half of the time into microplastics, so not quite the same. So, left with no choice, I run my own tests but it is not supposed to be like that.

At €1.55–€1.95 per pack (around €0.02 per wipe), the pricing aligns with conventional alternatives. However, without material transparency, responsible disposal becomes guesswork. While I have disposed of these wipes in organic waste and compost heaps, their actual degradation performance remains unverified.

El Corte Inglés states a commitment to sustainability online, but its environmental efforts appear largely focused on fashion, furniture, and electronics recycling. Within grocery and household supplies, meaningful action is still limited. Their wet wipes are functional and affordable, but sustainability remains unproven. I am looking for more serious alternatives, but for now, I am using these responsibly. We ask for "True compostable wipes" made with 100% cellulose and certified (e.g. EN 13432).

Comments